Table of Contents

Early Life

Childhood

William Samuel Clouston Stanger, the son of William Hunter Stanger, an immigrant from Orkney who worked in a flour mill at Point Douglas (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada), and his wife, Sarah Johnston, was born in Winnipeg, Canada on January 23rd, 1897. His father died in 1901 his mother was left to bring up three young children.

Bina Ingimundson told Bill Macdonald: “When her husband died, she had three children. There was no way she could support them. So she gave Bill to my aunt.” Bina’s aunt was Kristin Stephenson, the wife of Vigfus Stephenson, a labourer in a lumber yard. In recognition of this he took the name of his adopted parents.

Stephenson was educated at Argyle Elementary School. One of his teachers, Jean Moffat, later recalled:

“William Stephenson was a bookworm… who loved boxing. A wee fellow, but a real one for a fight. Of course, you see, he was the man of the house since the time he was a toddler.” After leaving school he worked in a lumber yard, and then delivered telegrams for Great North West Telegraph.

Famous Murder Case

Source: Archives of Manitoba

In December 1913 he became involved in a famous murder case. John Krafchenko, a man with a long criminal record, shot dead Henry Medley Arnold, the manager of the Bank of Montreal in Plum Coulee, Manitoba. A watch found in the getaway car was traced through a pawnshop’s records to being owned by Krafchenko. The local newspaper reported that Krafchenko “has a genius for robberies requiring desperate action”. Another report claimed that Krafchenko was “one of the most cultured men imaginable”. Krafchenko went into hiding in a house in Winnipeg. It was while delivering telegrams Stephenson spotted the wanted man and reported it to the police. Stephenson followed the trial of Krafchenko with great interest and was fascinated to discover that he confessed to having a fountain pen filled with itroglycerine. He intended to use it as a bomb in order to avoid capture. During the trial he escaped from prison but was caught soon after. Five other men were taken into custody for aiding his escape, including his attorney, a legal clerk, a former building trade official and a prison guard. The local newspaper reported that his accomplices were “under the spell of his fascinating personality”. Krafchenko was executed in 1914.

Military Career

First World War

Stephenson was determined to get involved in the First World War. On 12th January 1916, he enlisted in the Winnipeg Light Infantry. According to the doctor who examined him he had brown eyes, dark hair, a dark complexion, five foot two inches tall with a 32-inch expanded girth. He was considered to be too small to be a soldier and the medical officer wrote “passed as bugler” on his papers. Stephenson received basic training in Winnipeg before being sent by boat to Britain, arriving on 6th July, 1916.

Stephenson arrived on the Western Front later that month. He was wounded during a gas attack less than a week later and was returned to England to convalesce at Shorncliffe. It took him several months to recover his fitness. Instead of being sent back to France he was sent on courses in the theory of flight, internal combustion engines, communications and navigation. In April 1917 he was promoted to the rank of sergeant and joined the Cadet Wing of the Royal Flying Corps for training as a pilot.

In February, 1918, Stephenson was sent to France where he joined the 73 Squadron. Soon after arriving he met Gene Tunney. Both men were keen on boxing and Stephenson won the featherweight championship of the Inter Allied Games at Amiens. Tunney said later: “Everybody admired him. He was quick as a dash of lightning. He was a fast, clever featherweight… he was a fearless and quick thinker.”

Stephenson’s Sopwith Camel was attacked by two enemy aircraft in March 1918 and was severely damaged. He landed out of control and was nearly killed. According to H. Montgomery Hyde, the author of The Quiet Canadian (1962): “He immediately got into another machine and the first thing we knew there was a report that he shot down two Germans.” The following month he was awarded the Military Cross. It was later recorded: “When flying low and observing an open staff car on a road, he attacked it with such success that later it was seen lying in the ditch upside down. During the same flight, he caused a stampede amongst some enemy transport horses on a road. Previous to this, he had destroyed a hostile scout and a two-seater plane. His work has been of the highest order and he has shown the greatest courage and energy in engaging every kind of target.”

There has been some dispute over exactly how many enemy aircraft were shot down by William Stephenson. Cross and Cockade International, a First World War aviation society, Stephenson shot down a total of 12 aircraft. However, a French newspaper reported in 1918 that he had shot down eighteen aircraft and two kite balloons. His achievements were acknowledged when he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1918.

Imprisonment and Escape

On 28th July 1918, Stephenson was reported missing. The French newspaper Avion commented: “It appears that on the afternoon of July 28th, Captain Stephenson, decided to make a lone patrol of the line. Regular Scout patrols had been canceled for the day owing to stormy weather. About four miles within the Bosche Lines… one of our reconnaissance machines was being attacked by seven Fokker Biplanes which had been hiding in the dense clouds a few hundred metres above. According to American balloon observers, a British machine of the pattern Stephenson flew suddenly dived out of the clouds and without hesitation attacked the leader of the enemy formation, shooting him down in flames. There followed a terrific battle in which the daring captain made excellent strategic use of the clouds and succeeded in shooting down another German machine, while a third went spinning to the ground out of control.” The report then went on to explain that Stephenson was shot down. “France has good reason to cherish the memory of this brilliant young Canadian pilot and to pray that he descended alive.”

Stephenson’s friend, Tommy Drew-Brook, explained what had happened: “The unfortunate French

observer saw this machine out of the corner of his eye, spun his gun and fired a burst into Bill, which killed his engine and put one bullet through his leg. He landed just in front of the German front line, crawled out of his machine, and headed for our lines, but unfortunately a German gunner hit him again in the same leg and that stopped him and resulted in him being captured.”

While in the prison camp, Stephenson stole a German tin opener. Stephenson was impressed with performance of the tin opener and told Drew-Brook that he planned to escape from the camp as soon as possible, and he was going to take the can opener with him, and patent it in every country in the world. He did manage to escape and by 1919 he was back in Winnipeg selling can openers. Drew-Brook later recalled: “He took the can opener with him, and I think he did patent it and I believe was successful in making considerable money out of it.”

Post War Ventures

Entrepreneurship and Broadcasting Innovations

In January 1921 Stephenson formed a business partnership with Charles Wilfred Russell “to carry on

the business of Manufacturers Agents, Exporters and Importers of hardware goods, cutlery, auto accessories, groceries, timber, and goods, wares and merchandise of every description.” The main

purpose was to sell can openers but in recession hit Canada this was not an easy task and in August, 1922, the partners filed for bankruptcy. Owing a large amount of money Stephenson fled to England. Joan Morrison recalled: “He left in a rather bad odour. He got money from many people in the Icelandic community, and didn’t pay it back. Then he left town in the dark of the night.”

Stephenson started up a new company at 28 South Audley Street. He joined up with T. Thorne Baker, who was carrying out research into photo-telegraphy. Both men began work in developing a machine that could send photos over telephone lines. Stephenson later told Harford Montgomery Hyde that they developed a “light sensitive device” that increased the rate of transmission.Stephenson realized that if the process was sped up even further, moving pictures could be transmitted. In other words, television sets.

On 28th August 1923, The Manitoba Free Press reported: “Due partly to his efforts and a tremendous

advertising campaign, broadcasting was established in England on a highly efficient and comprehensive scale within a few short months and his companies were the first in England to produce a complete range of broadcasting equipment suitable for public use.” The Daily Mail, who had made use of this technology, described Stephenson as a “brilliant scientist” and credited him with “a leading role in the revolutionary transmission of wireless photography”. According to a newspaper in South Carolina, Stephenson predicting “moving pictures… may soon be possible to see… at one’s home.”

In 1923 Stephenson became the managing director of the General Radio Company Limited and the Cox Cavendish Electrical Company. The companies manufactured radios at Twyford Abbey Works on Acton Lane in Harlesden and had showrooms at 105 Great Portland Street for their wireless, X-ray and electro-medical supplies. Another newspaper claimed that “Stephenson… devoted himself to solving the problem of the wireless transmission of photographs and television… He has gone a long way toward the solution of these problems and has been successful in transmitting photographs by wireless suitable for newspaper reproduction.”

Marriage and Personal Life

Stephenson met Mary Simmons on board a boat returning from a business trip to New York City. Mary was the daughter of William H. Simmons, of Springfield, Tennessee. The couple married on 22nd July 1924 at Emperor’s Gate Presbyterian Church, South Kensington. None of Stephenson’s parents were present at the wedding. The New York Times reported on 31st August that Mary Simmons had married “Captain William Samuel Stephenson, inventor of a device to send photographs by radio.” Marion de Chastelain knew the Stephensons and later recalled: “Mary was just the right size for him because Bill was quite short and she was even shorter. I felt tall tall when I was next to her.”

Other Business Ventures

Richard Deacon, the author of Spyclopaedia: The Comprehensive Handbook of Espionage (1987), has pointed out: “After the war he became a pioneer in broadcasting and especially in the radio transmission of photographs. By the 1930s he had become an important man involved in broadcasting developments in Canada, in a film company in London, the manufacture of plastics and the steel industry.”

In 1934 Stephenson hired Flight Lieutenant H. M. Schofield to fly a plane produced by his General Aircraft Limited to win the King’s Cup air race with an average speed of 134.16 miles an hour in poor weather conditions.

Stephenson received the financial backing of Charles Jocelyn Hambro. This enabled him to take control of Alpha Cement, which was one of the largest cement companies in Britain. He also established Sound City films and built Shepperton Studios. It eventually became the largest film studios outside Hollywood. In 1936 Stephenson joined the board of Pressed Steel Company, which made 90 percent of Britain’s car bodies. Stephenson told Thomas F. Troy that he purchased it from Edward G. Budd Company of Philadelphia for $13 million.

Roald Dahl considered Stephenson to have a brilliant mind: “There’s no question about that, I mean the fact he became a millionaire about the same time as Lord Beaverbrook and at about the same age, 27 or 28. Came over here and took over Pressed Steel at that age… and it was not so easy to become a millionaire as it is today. He became rich as soon as he wanted to, more or less.”

A Career in Espionage

Formation of Intelligence Organization

Gill Bennett has claimed that he “built up a highly successful career as a businessman, becoming a millionaire through enterprises such as the Pressed Steel Company, which apparently made ninety percent of car bodies for British automobile manufacturers.” While on a business trip in Nazi Germany he discovered that practically the whole of German steel production had been turned over to armament manufacture. Stephenson decided to create his own private clandestine industrial intelligence organization. He then offered his services to the British government. He was put into contact with MI6 which was initially not very enthusiastic. Undeterred, Stephenson set up the International Mining Trust (IMT) in Stockholm, “under cover of which he aimed to develop contacts into Germany and elsewhere to provide industrial and other intelligence.”

Information about the Nazi Threat

According to Charles Howard Ellis, a British intelligence officer, Stephenson began “providing a great deal of information on German rearmament” to Winston Churchill. He went on to argue that although Churchill was not in office, “He was playing quite an important role in providing background information. There were members of the House of Commons who were much more concerned about what was happening than the administration seemed to be at that time.”

Roald Dahl has argued that Stephenson was a close friend of Lord Beaverbrook during this period: “He did not know Churchill personally then… with his absolute cleverness, he spotted Churchill as a future leader…. He could have sent them to Halifax or Chamberlain. But they were both idiots, and he wouldn’t have got anywhere… I think Max Beaverbrook advised him to do it, too, because they were both Canadians. He was a close friend, a really genuinely close friend of Beaverbrook.”

The author of A Man Called Intrepid (1976) was told by Stephenson that he met with German military and aviation officials as early as 1934. At these meetings he is said to have learned more about Nazi doctrine and about the strategy of Blitzkreig. He was told, “the real secret is speed – speed of attack, through speed of communications”. Stephenson passed this information on to Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, the 7th Marquess of Londonderry, who was Secretary of State for Air, under Ramsay MacDonald. The minister failed to take action, as he was sympathetic to the Adolf Hitler regime. He told Joachim von Ribbentrop in February 1936: “As I told you, I have no great affection for the Jews. It is possible to trace their participation in most of those international disturbances which have created so much havoc in different countries.”

Stephenson eventually got this information to the British government and the new prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, moved the Marquess of Londonderry to leader of the House of Lords. A member of British Intelligence, Frederick William Winterbotham, and another Nazi sympathiser, wrote in his book, The Nazi Connection (1978): “Poor Lord Londonderry had been Baldwin’s scapegoat. A most delightful man, I’d always felt that he was far too sensitive to be in the hurly-burly of politics in the thirties.”

Reporting to Winston Churchill

Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001) has suggested that this information was passed to Desmond Morton, the head of the Industrial Intelligence Centre, who reported to Churchill. Richard Deacon has pointed out: “Only one man as willing to give him a ready ear and find out more – Winston Churchill. From then until the outbreak of war Stephenson became one of a small, unofficial team who supplied Churchill with intelligence on Germany.” The author of Churchill’s Man of Mystery (2009) doubts the truth of this story: “Although claims that he secretly furnished details of German rearmament to Churchill during the interwar period seem dubious, it is true that he built up an international network of contacts and informants concerned principally with obtaining secret industrial information to enable financial houses to judge the advisability of pursuing business propositions.”

In 1937 Stephenson reported on Reinhard Heydrich: “The most sophisticated apparatus for conveying top-secret orders was at the service of Nazi propaganda and terror. Heydrich had made a study of the Russian OGPU, the Soviet secret security service. He then engineered the Red Army purges carried out by Stalin. The Russian dictator believed his own armed forces were infiltrated by German agents as a consequence of a secret treaty by which the two countries helped each other rearm. Secrecy bred suspicion, which bred more secrecy, until the Soviet Union was so paranoid it became vulnerable to every hint of conspiracy.”

Plan to Assassinate Hitler

According to Anthony Cave Brown, the author of The Secret Life of Sir Stewart Graham Menzies (1987), Stephenson came up with a plan in 1938 to assassinate Adolf Hitler with a high-powered sporting rifle at a Nazi rally. He suggested arming a “young English crack-shot with high powered telescopic sighted rifle”. However, the plan was vetoed by Britain’s foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, the leading exponent of appeasement. Instead, Neville Chamberlain, decided to negotiate with Hitler and he signed the Munich Agreement in September 1938.

The British Industrial Secret Service

Stephenson eventually established the British Industrial Secret Service (BISS) and offered it to the British government. Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service: 1909-1949 (2010), has seen evidence of Stephenson working with the government: “Closer links were established after Dick Ellis began developing the 22000 network, and up to the outbreak of the war the IMT proved quite useful in providing information on German armament potential.”

Ralph Glyn, the member of the House of Commons for Abingdon, arranged for Stephenson to meet leading figures at the Foreign Office. The meeting took place on 12th July, 1939. The official noted: “He is a Canadian with a quiet manner, and evidently knows a great deal about Continental affairs and industrial matters. During a short discussion on the oil and non-ferrous metal questions he showed that he possesses a thorough grasp of the situation.” Desmond Morton described his information as invaluable and by September 1939, agreement was reached for BISS (now known as Industrial Secret Intelligence – ISI) to pass information to the Secret Intelligence Service.

British Security Coordination

Formation of the British Security Coordination (BSC)

Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. He realised straight away that it would be vitally important to enlist the United States as Britain’s ally. He sent Stephenson to the United States to make certain arrangements on intelligence matters. Stephenson’s main contact was Gene Tunney, a friend from the First World War, who had been World Heavyweight Champion (1926-1928) and was a close friend of J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI. Tunney later recalled: “Quite to my surprise I received a confidential letter that was from Billy Stephenson, and he asked me to try and arrange for him to see J. Edgar Hoover… I found out that his mission was so important that the Ambassador from England could not be in on it, and no one in official government… It was my understanding that the thing went off extremely well.”

Stephenson was also a friend of Ernest Cuneo. He worked for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and according to Stephenson was the leader of “Franklin’s brain trust”. Cuneo met with Roosevelt and reported back that the president wanted “the closest possible marriage between the FBI and British Intelligence.” On his return to London, Stephenson reported back to Churchill. After hearing what he had to say, Churchill told Stephenson: “You know what you must do at once. We have discussed it most fully, and there is a complete fusion of minds between us. You are to be my personal representative in the United States. I will ensure that you have the full support of all the resources at my command. I know that you will have success, and the good Lord will guide your efforts as He will ours.” Charles Howard Ellis said that he selected Stephenson because: “Firstly, he was Canadian. Secondly, he had very good American connections… he had a sort of fox terrier character, and if he undertook something, he would carry it through.”

Churchill now instructed Stewart Menzies, head of MI6, to appoint Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC). Menzies told Gladwyn Jebb on 3rd June, 1940: “I have appointed Mr W.S. Stephenson to take charge of my organisation in the USA and Mexico. As I have explained to you, he has a good contact with an official (J. Edgar Hoover) who sees the President daily. I believe this may prove of great value to the Foreign Office in the future outside and beyond the matters on which that official will give assistance to Stephenson. Stephenson leaves this week. Officially he will go as Principal Passport Control Officer for the USA.”

As William Boyd has pointed out: “The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history… With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated – eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak… polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe.

Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention. An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI. Bill Ross Smith, who worked for British Security Coordination in New York City, has argued: “Stephenson was exactly the right man, because he had all these terrific contacts and had this tremendous flair of influencing people, in an incredibly quiet way. If he could walk into this room now, he could sit down in that chair and, without saying a word, dominate this room. I tell you he was absolutely, bloody well a genius… He was no James Bond because he didn’t go around killing people with his bare hands, or even with a gun. He dealt strictly with his brain and personality.”

Council for Democracy: Countering American Isolationism

Winston Churchill had a serious problem. Joseph P. Kennedy was the United States Ambassador to Britain. He soon came to the conclusion that the island was a lost cause and he considered aid to Britain fruitless. Kennedy, an isolationist, consistently warned Roosevelt “against holding the bag in a war in which the Allies expect to be beaten.” Neville Chamberlain wrote in his diary in July 1940: “Saw Joe Kennedy who says everyone in the USA thinks we shall be beaten before the end of the month.” Averell Harriman later explained the thinking of Kennedy and other isolationists: “After World War I, there was a surge of isolationism, a feeling there was no reason for getting involved in another war… We made a mistake and there were a lot of debts owed by European countries. The country went isolationist.

In July, 1940, Henry Luce, C. D. Jackson, Freda Kirchwey, Raymond Gram Swing, Robert Sherwood, John Gunther and Leonard Lyons, Ernest Angell and Carl Joachim Friedrich established the Council for Democracy in July, 1940. According to Kai Bird the organization “became an effective and highly visible counterweight to the isolation rhetoric” to America First Committee led by Charles Lindbergh and Robert E. Wood: “With financial support from Douglas and Luce, Jackson, a consummate propagandist, soon had a media operation going which was placing anti-Hitler editorials and articles in eleven hundred newspapers a week around the country.” The isolationist Chicago Tribune accused the Council for Democracy of being under the control of foreigners: “The sponsors of the so-called Council for Democracy… are attempting to force this country into a military adventure on the side of England.”

According to The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45, a secret report written by leading operatives of the British Security Coordination (Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill), Stephenson played an important role in the formation of the Council for Democracy: “William Stephenson decided to take action on his own initiative. He instructed the recently created SOE Division to declare a covert war against the mass of American groups which were organized throughout the country to spread isolationism and anti-British feeling.

In the BSC office plans were drawn up and agents were instructed to put them into effect. It was agreed to seek out all existing pro-British interventionist organizations, to subsidize them where necessary and to assist them in every way possible. It was counter-propaganda in the strictest sense of the word. After many rapid conferences the agents went out into the field and began their work. Soon they were taking part in the activities of a great number of interventionist organizations, and were giving to many of them which had begun to flag and to lose interest in their purpose, new vitality and a new lease of life. The following is a list of some of the larger ones… The League of Human Rights, Freedom and Democracy… The American Labor Committee to Aid British Labor… The Ring of Freedom, an association led by the publicist Dorothy Thompson, the Council for Democracy; the American Defenders of Freedom, and other such societies were formed and supported to hold anti-isolationist meetings which branded all isolationists as Nazi-lovers.”

Transferring American Destroyers to the Royal Navy

Stephenson knew that with leading officials supporting isolationism he had to overcome these barriers. His main ally in this was another friend, William Donovan, who he had met in the First World War. “The procurement of certain supplies for Britain was high on my priority list and it was the burning urgency of this requirement that made me instinctively concentrate on the single individual who could help me. I turned to Bill Donovan.” Donovan arranged meetings with Henry Stimson (Secretary of War), Cordell Hull (Secretary of State) and Frank Knox (Secretary of the Navy). The main topic was Britain’s lack of destroyers and the possibility of finding a formula for transfer of fifty “over-age” destroyers to the Royal Navy without a legal breach of U.S. neutrality legislation.

It was decided to send Donovan to Britain on a fact-finding mission. He left on 14th July, 1940. When he heard the news, Joseph P. Kennedy complained: “Our staff, I think is getting all the information that possibility can be gathered, and to send a new man here at this time is to me the height of nonsense and a definite blow to good organization.” He added that the trip would “simply result in causing confusion and misunderstanding on the part of the British”. Andrew Lycett has argued: “Nothing was held back from the big American. British planners had decided to take him completely into their confidence and share their most prized military secrets in the hope that he would return home even more convinced of their resourcefulness and determination to win the war.”

William Donovan arrived back in the United States in early August, 1940. In his report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt he argued: “(1) That the British would fight to the last ditch. (2) They would not hope to hold to hold the last ditch unless they got supplies at least from America. (3) That supplies were of no avail unless they were delivered to the fighting front – in short, that protecting the lines of communication was a sine qua non. (4) That Fifth Column activity was an important factor.” Donovan also urged that the government should sack Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, who was predicting a German victory. Donovan also wrote a series of articles arguing that Nazi Germany posed a serious

threat to the United States.

On 22nd August, Stephenson reported to London that the destroyer deal was agreed upon. The agreement for transferring 50 aging American destroyers, in return for the rights to air and naval basis in Bermuda, Newfoundland, the Caribbean and British Guiana, was announced 3rd September, 1940. The bases were leased for 99 years and the destroyers were of great value as convey escorts. Lord Louis Mountbatten, the British Chief of Combined Operations, commented: “We were told that the man primarily responsible for the loan of the 50 American destroyers to the Royal Navy at a critical moment was Bill Stephenson; that he had managed to persuade the president that this was in the ultimate interests of America themselves and various other loans of that sort were arranged. These destroyers were very important to us…although they were only old destroyers, the main thing was to have combat ships that could actually guard against and attack U-boats.”

Contending with the American First Committee

Stephenson was very concerned with the growth of the American First Committee. by the spring of 1941, the British Security Coordination (BSC) estimated that there were 700 chapters and nearly a million members of isolationist groups. Leading isolationists were monitored, targeted and harassed. When Gerald Nye spoke in Boston in September 1941, thousands of handbills were handed out attacking him as an appeaser and Nazi lover. Following a speech by Hamilton Stuyvesan Fish, a member of a group set-up by the BSC, the Fight for Freedom, delivered him a card which said, “Der Fuhrer thanks you for your loyalty” and photographs were taken.

A BSC agent approached Donald Chase Downes and told him that he was working under the direct orders of Winston Churchill. “Our primary directive from Churchill is that American participation in the war is the most important single objective for Britain. It is the only way, he feels, to victory over Nazism.” Downes agreed to work for the BSC in spying on the American First Committee. He was also instructed to find information on German consulates in Boston and Cleveland and the Italian consulate in the capital. He later recalled in his autobiography, The Scarlett Thread (1953) that he received assistance in his work from the Jewish Anti-Defamation League, Congress for Industrial Organisation and U.S. army counter-intelligence. Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001), has pointed out: “Downes eventually discovered there was Nazi activity in New York, Washington, Chicago, San Francisco, Cleveland and Boston. In some cases they traced actual transfers of money from the Nazis to the America Firsters.”

Collaboration with American Intelligence

One of his earliest contacts was Robert E. Sherwood. In his book, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948) he argued: “There was established by Roosevelt’s order and despite State Department qualms, effectively close cooperation between J. Edgar Hoover and British Security Services under the direction of a quiet Canadian, William Stephenson.”

Charles Howard Ellis was sent to New York City to work alongside William Stephenson as assistant director. Together they recruited several businessmen, journalists, academics and writers into the British Security Coordination. This included Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce, Charles Howard Ellis, Noël Coward, David Ogilvy, Paul Denn, Eric Maschwitz, Cedric Belfrage, Giles Playfair, Benn Levy, Sydney Morrell and Gilbert Highet.

The CIA historian, Thomas F. Troy has argued: “BSC was not just an extension of SIS, but was in fact a service which integrated SIS, SOE, Censorship, Codes and Ciphers, Security, Communications – in fact nine secret distinct organizations. But in the Western Hemisphere Stephenson ran them all.”

Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle reported to Sumner Welles on 31st March, 1941, that “the head of the field service appears to be Mr. William S. Stephenson… in charge of providing protection for British ships, supplies etc. But in fact a full size secret police and intelligence service is rapidly evolving… with district officers at Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, New Orleans, Houston, San Francisco, Portland and probably Seattle.”

Over the next few years Stephenson worked closely with William Donovan, the chief of the Office of Strategic Service (OSS). Gill Bennett has argued: “Each is a figure about whom much myth has been woven, by themselves and others, and the full extent of their activities and contacts retains an element of mystery. Both were influential: Stephenson as head of British Security Coordination (BSC),

the organisation he created in New York at Menzies’s request and Donovan, working with Stephenson as intermediary between Roosevelt and Churchill, persuading the former to supply clandestine military supplies to the UK before the USA entered the war, and from June 1941 head of the COI and thus one of the architects of the US Intelligence establishment.”

Grace Garner, Stephenson’s secretary, claimed he recruited several journalists including Sydney Morrell from the Daily Express and Doris Sheridan, from the Daily Mirror. “This was propaganda, or at least putting forward the British case. Sheridan liaised with the Arab sections in New York, keeping in touch with foreign nationals. The English playwright Eric Maschwitz was recruited to write propaganda and scripts. University professor Bill Deaken worked for the office, as well as the philosopher A. J. Ayer.” Cedric Belfrage and Gilbert Highet were also recruited by Stephenson: “Belfrage was brought in as one of the propaganda people… he was a known communist… Gilbert Highet was in propaganda with Belfrage.” John D. Bernal, used to call in the office. Garner described as a “dead ringer” for Harpo Marx. “You could have walked him straight onto the set. Wild. He had a funny hat on, and this saggy, greeny old coat, bulging with documents.”

Grace Garner enjoyed working with Stephenson: “He had very dark, piercing eyes and the uncanny stillness of the man. When he walked he was very quiet and still… He had that quality of blending into a crowd. He certainly took in things in an instant, and he got to the centre of a thing. He would not put up with long documents… He wouldn’t stand for gobbledygook… His English was flawless,

his style was terse, tense and to the point… He was a very small in stature, neat man and very neatly

put together, doesn’t move his hands or do anything like that. A very still person.. He walked like a

black panther… He moved fast, but it was silent…. He didn’t like tall people. He said their brains were

too far from their feet.”

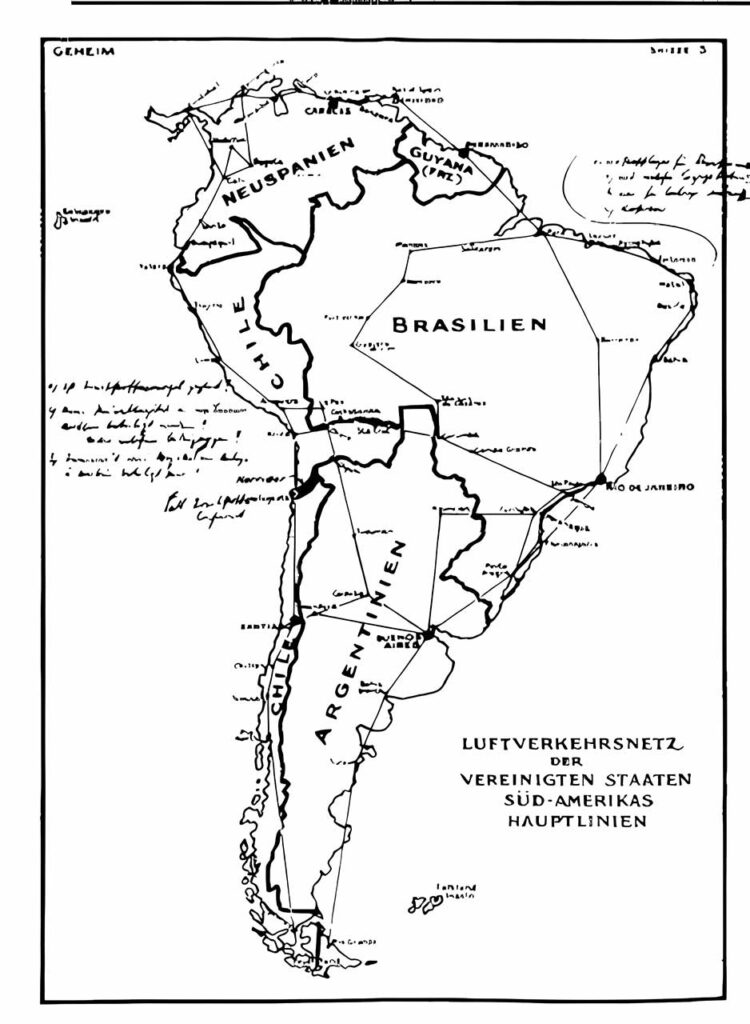

The Phony Document Operation

One of Stephenson’s agents was Ivar Bryce. According to Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998): “Bryce worked in the Latin American affairs section of the BSC, which was run by Dickie Coit (known in the office as Coitis Interruptus). Because there was little evidence of the German plot to take over Latin America, Ivar found it difficult to excite Americans about the threat.”

Nicholas J. Cull, the author of Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign Against American Neutrality (1996), has argued: “During the summer of 1941, he (Bryce) became eager to awaken the United States to the Nazi threat in South America.” It was especially important for the British Security Coordination to undermine the propaganda of the American First Committee. Bryce recalls in his autobiography, You Only Live Once (1975): “Sketching out trial maps of the possible changes, on my blotter, I came up with one showing the probable reallocation of territories that would appeal to Berlin. It was very convincing: the more I studied it the more sense it made… were a genuine German map of this kind to be discovered and publicised among… the American Firsters, what a commotion would be caused.”

Stephenson, who once argued that “nothing deceives like a document”, approved the idea and the project was handed over to Station M, the phony document factory in Toronto run by Eric Maschwitz, of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). It took them only 48 hours to produce “a map, slightly travel-stained with use, but on which the Reich’s chief map makers… would be prepared to swear was made by them.” Stephenson now arranged for the FBI to find the map during a raid on a German safe-house on the south coast of Cuba. J. Edgar Hoover handed the map over to William Donovan. His executive assistant, James R. Murphy, delivered the map to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The historian, Thomas E. Mahl argues that “as a result of this document Congress dismantled the last of the neutrality legislation.”

Nicholas J. Cull has argued that Roosevelt should not have realised it was a forgery. He points out that Adolf A. Berle, the Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs, had already warned Cordell Hull, the Secretary of State that “British intelligence has been very active in making things appear dangerous in South America. We have to be a little on our guard against false scares.”

Information about Pearl Harbour Attack

British Security Coordination (BSC) managed to record the conversations of Japanese special envoy Suburu Kurusu with others in the Japanese consulate in November 1941. Marion de Chastelain was the cipher clerk who transcribed these conversations. On 27th November, 1941, William Stephenson sent a telegram to the British government: “Japanese negotiations off. Expect action within two weeks.” According to Roald Dahl, who worked for BSC: “Stephenson had tapes of them discussing the actual date of Pearl Harbor… and he swears that he gave the transcription to FDR. He swears that they knew therefore of the oncoming attack on Pearl Harbor and hadn’t done anything about it.”

BSC’s Operations and Influence

Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001) has pointed out: “Although they were called British Security Coordination, the Stephenson people were very much a law unto themselves. They made many separate deals with other countries and distributed information amongst the three Western Allies. They controlled many of the secrets of the three countries, including ULTRA and MAGIC, and also had communication influence in the South Pacific and Asia. There were a number of British appointments at BSC, but essentially, Stephenson contacted his friends, put them to work, and had them find staff… The important work these people accomplished during the war has never been fully explored.”

On 13th February, 1942, Adolph Berle received information from the FBI that a BSC agent, Dennis Paine, had been investigating him in order to “get the dirt” on him. Paine was expelled from the United States. Stephenson believed that Paine had been set-up as part of a FBI public relations exercise. He later recalled: Adolf Berle was slightly school-masterish for a very brief period due to misinformation, but could not have been more helpful when factual situation was clarified to him.”

William Boyd has argued the BSC “became a huge secret agency of nationwide news manipulation and black propaganda. Pro-British and anti-German stories were planted in American newspapers and broadcast on American radio stations, and simultaneously a campaign of harassment and denigration was set in motion against those organisations perceived to be pro-Nazi or virulently isolationist”.

Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service: 1909-1949 (2011) has

pointed out: “The New York organisation expanded well beyond pure intelligence matters, and eventually combined the North American functions not just of SIS, but of M15, SOE and the Security Executive (which existed to co-ordinate counter-espionage and counter-subversion work): intelligence, security, special operations and also propaganda. Agents were recruited to target enemy or enemy controlled businesses, and penetrate Axis (and neutral) diplomatic missions; representatives were posted to key points, such as Washington, New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle; American journalists, newspapers and news agencies were targeted with pro-British material; an ostensibly independent radio station (WURL), with an unsullied reputation for impartiality, was virtually taken over.”

William Donovan, the chief of the Office of Strategic Service (OSS) has called the British Security Coordination (BSC) “the greatest integrated secret intelligence and operations organization that has ever existed anywhere”. David Bruce, who was a member of the OSS has argued: “Had it not been for Stephenson’s achievements it seems to me highly possible that the Second World War would have followed a different and perhaps fatal course.”

Post WWII

Camp X

At the end of the Second World War the files of British Security Coordination were packed onto semitrailers and transported to Camp X in Canada. Stephenson wanted to have some record of the activities of the agency, “To provide a record which would be available for reference should future need arise for secret activities and security measures for the kind it describes.” He recruited Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill, to write the book. Stephenson told Dahl: “We don’t dare to do it in the United States, we have to do it on British territory.” Dahl commented: “He (Stephenson) pulled a lot over Hoover… He pulled a few things over the White

House, too, now and again. I wrote a little bit but eventually I called Bill and told him that it’s an historian’s job… This famous history of the BSC through the war in New York was written by Tom Hill

and a few other agents.” Only twenty copies of the book were printed. Ten went into a safe in Montreal and ten went to Stephenson for distribution.

Uncovering Soviet Espionage

In September 1945, Stephenson was told about Igor Gouzenko, a Soviet Embassy cipher clerk who was also working for Soviet military intelligence, who wanted to defect. Gouzenko later wrote: “During my residence in Canada, I have seen how the Canadian people and their government, sincerely wishing to help the Soviet people sent supplies to the Soviet Union, collected money for the welfare of the Russian people, sacrificing the lives of their sons in the delivery of supplies across the ocean – and instead of gratitude for the help rendered, the Soviet government is developing espionage activity in Canada, preparing to deliver a stab in the back to Canada – all this without the knowledge of the Russian people.”

Stephenson arranged for Gouzenko to be taken into protective custody. He was then transferred to Camp X, where he and his wife lived in guarded seclusion. Later two former BSC agents interviewed him. Gousenko’s evidence led to the arrest of Klaus Fuchs and Alan Nunn May and 17 others in 1946. As Bill Macdonald has pointed out: “He (Gouzenko) is regarded as the most important defector of the era, and his revelations are often regarded as the beginning of the Cold War.”

World Commerce Corporation

After the war Stephenson bought a house, Hillowton, on Jamaica overlooking Montego Bay. His close friends, Lord Beaverbrook, William Donovan, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce and Noël Coward, also purchased property on the island. Roald Dahl has argued that Stephenson was very close to Beaverbrook during this period: “He was a close friend, a really genuinely close friend of Beaverbrook. I’ve been in Beaverbrook’s house in Jamaica with him and they were absolutely like that (crossing his fingers)… A couple of old Canadian millionaires who were both pretty ruthless.” He also kept in close contact with Henry Luce, Hastings Ismay and Frederick Leathers. His friends recalled that he was drinking heavily. Marion de Chastelain commented that “he made the wickedest martini that was ever made”. Coward referred to him often having “too many martinis”.

In 1951 Stephenson sold Hillowton and moved to New York City. Soon afterwards he was appointed chairman of the Newfoundland and Labrador Corporation, by the Canadian province’s first premier, Joey Smallwood. He helped attract new industries and investment but resigned in October 1952 because he thought the corporation should have a local head. Smallwood accepted his resignation with reluctance and regret: “You achieved a magnificent result in a very short space of time, and I and the Government and people of Newfoundland must ever be grateful to you.”

Stephenson also set up the British-American-Canadian-Corporation (later called the World Commerce Corporation) with William Donovan. It was a secret service front company which specialized in trading goods with developing countries. William Torbitt has claimed that it was “originally designed to fill the void left by the break-up of the big German cartels which Stephenson himself had done much to destroy.” Most of the leading figures in the company were formerly in the British Security Coordination (BSC) and the Office of Strategic Service (OSS). The company used barter agreements and dollar guarantees to get around currency restrictions that slowed world trade. Tom Hill, who worked for the World Commerce Corporation later recalled: “The idea was to take advantage of the organization and international contacts that were set up during the war… The goal was to set up various companies, mostly in Central and South America.”

Roald Dahl argues that the original idea came from David Ogilvy who argued that “we all needed jobs in civilian life.” Dahl claims that Stephenson liked the idea and circulated copies of Ogilvy’s paper to some of the wealthy people he worked with during the war and some of them put up capital. Other people involved in the organization included Lord Beaverbrook, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce, Henry Luce, Nelson Rockefeller, John McCloy, Edward Stettinius, Charles Hambro, Richard Mellon, Victor Sassoon, Roundell Palmer, Ralph Glyn, Frederick Leathers, William Rootes, Alexander Korda, Campbell Stewart (director of The Times) and Lester Armour. Another business associate during this period was William Formes-Sempill, who we now know was a Nazi spy during the Second World War. It has been suggested by Thomas F. Troy, a senior officer in the CIA, believed Stephenson continued to be involved in intelligence activities.

One of the successes of the World Commerce Corporation was to bring a cement industry to Jamaica. Stephenson became chairman of the board of the Caribbean Cement Company Limited. In a speech he gave to shareholders of 1961 the company declared a profit of over £600,000 and he said that since 1952 the total savings to the country as a result of domestic production were over £3 million.

William Stephenson Publications

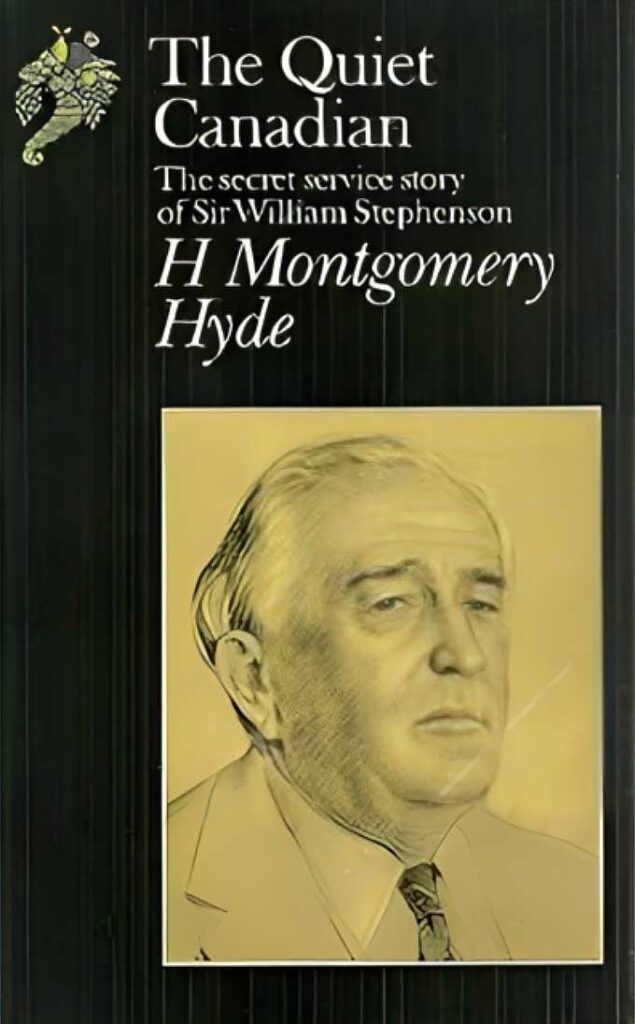

In the 1960s Stephenson commissioned H. Montgomery Hyde, to write The Quiet Canadian (1962) a

book about his work with the British Security Coordination. According to his biographer, David Hunt: “Its numerous invented stories, based on briefing from Stephenson, created a certain sensation but it still came short of Stephenson’s inflated ideas; and as fresh revelations of British successes in the intelligence sphere continued to appear – for instance the Ultra secret – he clearly wished to claim credit for them.” A classified CIA review said: “The publication of this study is shocking… Exactly what British intelligence was doing in the United States was closely held in Washington, and very little had hitherto been printed about it… One may suppose that Mr. Hyde’s account… is relatively accurate, but the wisdom of placing it on the public record is extremely questionable.”

Stephenson then commissioned William Stevenson (no relation of his), and provided him with a fund of fresh stories. A Man Called Intrepid was published in 1976. Hugh Trevor-Roper, a former intelligence officer, argued that the book was from “start to finish utterly worthless” and that Stephenson “was a fraud who fooled the world into believing he was a master spy”. David A. Stafford supported this view: “The amazing exploits of our favourite spymaster turned out to contain large doses of fiction concocted in the forgetful mind of an old man.”

David Hunt argues that the book “is almost entirely a work of fiction”. A.J.P. Taylor, wrote in the New Statesman: “Nearly everything in the book is either exaggerated, distorted or already known.” However, Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001), who has studied the life of Stephenson in great detail, admits that both books include factual mistakes, he played a very important role in British Intelligence during the Second World War.

The Decline of William Stephenson

Stephenson and his wife moved to Bermuda. Their friend, Marion de Chastelain, commented: “Mary didn’t particularly care for Bermuda… She loved New York and she had lots of friends…. she found Bermuda fairly boring… It must have been difficult for her, because Bill was not a man to socialize. You know, go to big parties.” Soon afterwards Stephenson suffered a stroke. Roald Dahl went to see him and was shocked by the way his speech was affected. Dahl was told his survival was uncertain. One day Ernest Cuneo told him, “we need you to fight the Reds.” Dahl claimed that he perked up after that.

Mary Stephenson died of cancer in 1977. Her full-time nurse, Elizabeth Baptiste and her son Rhys remained in Bermuda and looked after Stephenson. In 1983 Stephenson adopted Elizabeth as his

daughter. Marion de Chastelain objected to an article in a magazine by David A. Stafford that suggested Stephenson was senile by this time: “He wasn’t out of it at all. The impression of course could be due to his speech problem (after his stroke). Sometimes it was extremely good. And other times it wasn’t… that would give the impression that he wasn’t quite with it. You had to listen to what he said, not the way he said it.”

Thomas F. Troy, a staff officer of the CIA, interviewed Stephenson for his book, Wild Bill and Intrepid: Donovan, Stephenson and the Origins of the CIA (1996): “Stephenson, then 73, showed the effects of a stroke: a cane, shuffling feet, a slightly closed left eye, a curled upper lip, slightly slurred speech, and the years had made him heavier than the lightweight of old. But he smiled readily, his handshake was firm, his eyes were bright, his voice was strong, and his mind was active. Proof of his relative well being? On that first visit we and his wartime deputy sat in undisturbed lively conversation for fully four hours.”

William Stephenson died on 3rd January, 1989. He was buried in Bermuda in a secret ceremony at St. John’s Church. He told his adopted daughter before he died: “I don’t want people to know that I am dead until I am buried.”

Primary Sources

(1) William Stephenson’s Military Cross citation (22nd June, 1918).

When flying low and observing an open staff car on a road, he attacked it with such success that later it was seen lying in the ditch upside down. During the same flight, he caused a stampede amongst some enemy transport horses on a road. Previous to this, he had destroyed a hostile scout and a two-seater plane. His work has been of the highest order and he has shown the greatest courage and energy in engaging every kind of target.

(2) William Stephenson, head of the British Secret Intelligence Servicein the United States, report on

Reinhard Heydrich (1937)

The most sophisticated apparatus for conveying top-secret orders was at the service of Nazi

propaganda and terror. Heydrich had made a study of the Russian OGPU, the Soviet secret security

service. He then engineered the Red Army purges carried out by Stalin. The Russian dictator

believed his own armed forces were infiltrated by German agents as a consequence of a secret

treaty by which the two countries helped each other rearm. Secrecy bred suspicion, which bred

more secrecy, until the Soviet Union was so paranoid it became vulnerable to every hint of

conspiracy.

Late in 1936, Heydrich had thirty-two documents forged to play on Stalin’s sick suspicions and make

him decapitate his own armed forces. The Nazi forgeries were incredibly successful. More than half

the Russian officer corps, some 35,000 experienced men, were executed or banished.

The Soviet chief of Staff, Marshal Tukhachevsky, was depicted as having been in regular

correspondence with German military commanders. All the letters were Nazi forgeries. But Stalin

took them as proof that even Tukhachevsky was spying for Germany. It was a most devastating and

clever end to the Russo-German military agreement, and it left the Soviet Union in absolutely no

condition to fight a major war with Hitler.

(3) William Stephenson, A Man Called Intrepid (1976)

Churchill stumped up and down Reynaud’s bedroom. There was “the great probability that Hitler

will rule the world,” he said. We must think together of how to strike and strike again, no matter

what the cost nor how long the trials ahead.” He faced the French Premier and then sat down

heavily. His changing moods raced like clouds across his baby face. He was in turn sulky, tearful,

and violent. None of it did any good. Reynaud in reply chanted the pace of Hitler’s victories: Poland

in twenty-six days, Norway in twenty-eight days, Denmark in twenty-four hours, Holland in five days,

and Luxembourg in twelve hours. He turned sad luminous eyes on Churchill. “Belgium is finished.

Now France.”

(4) Gill Bennett, Churchill’s Man of Mystery (2009)

The story of the development of the Anglo-American Intelligence relationship, and in particular of

British influence on the establishment in July 1941 of the US Coordinator of Information (COI),

precursor of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) established in June 1942 and of the post-war

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), remains the subject of research and some speculation. At the

centre of the story and of the literature are two men who in the view of many (especially

themselves) came to symbolise the Anglo-American Intelligence relationship, “Little Bill”, later Sir

William Stephenson, and Major-General William “Wild Bill” Donovan. Each is a figure about whom

much myth has been woven, by themselves and others, and the full extent of their activities and

contacts retains an element of mystery. Both were influential: Stephenson as head of British

Security Coordination (BSC), the organisation he created in New York at Menzies’s request and

Donovan, working with Stephenson as intermediary between Roosevelt and Churchill, persuading

the former to supply clandestine military supplies to the UK before the USA entered the war, and

from June 1941 head of the COI and thus one of the architects of the US Intelligence establishment.

Morton’s part in the story was largely that of intermediary. Contemporary American observers, such

as US Ambassador in London Joseph Kennedy, his Military Attaché General Raymond E. Lee, and

Ernest Cuneo, a US lawyer with close intelligence and political connections, saw him as a “top level

operator”, a “discreet and shadowy figure” with a “through wire” to Churchill.” By this they meant

that he was the man to approach with an urgent message for the Prime Minister. In respect of

Stephenson and Donovan he was seen principally as a facilitator of what were assumed to be close

personal relationships with Churchill enjoyed by both men. However, the evidence suggests that

Churchill met Donovan on no more than one or two occasions, and may never have met

Stephenson at all. Any dealings with the Prime Minister were conducted almost exclusively through

Morton, a central point of contact. Churchill was uninterested in the detail of clandestine liaison

arrangements, being concerned principally with his own relationship with Roosevelt, and with

senior US representatives such as Harry Hopkins. He was also reluctant, in the summer of 1940 at

least, “to give our secrets until the United States is much nearer to the war than she is now”. He was

content to leave intelligence liaison with Stephenson, Donovan and others to Morton on a personal,

and Menzies on an operational, level.

It was, in fact, Menzies who was most effective in building the practical working relationship

between British and American intelligence (and thereby laying the foundations for US post-war

intelligence institutions). When Morton boasted to Colonel Ian Jacob in September 1941 that “to all

intents and purposes US security is being run for them at the President’s request by the British”, he

was referring to Stephenson and BSC: both reporting to Menzies. Stephenson, as we have seen, had

approached SIS in 1939, with Morton’s support, to secure Menzies’ sponsorship for his industrial

intelligence network.

No sooner had the arrangement been established satisfactorily in the spring of 1940, however, than

Stephenson turned his attention, at Menzies’s request, to exploring closer links with the US

authorities; in particular, to establishing a closer relationship between SIS and the Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI). Stephenson had spent much time in the US, where Menzies wished to increase

the scope of SIS operations, and to cooperate more closely with both official and less formal

authorities, establishing his own channels rather than, for example, going through M15 to the FBI.

At this stage there was no central coordination of “US Intelligence” in any institutional form, only

disconnected and rival bodies that sought to draw on the experience of their British analogues:

Menzies wanted it to be he, and SIS, that provided it.

(5) Stewart Menzies to Gladwyn Jebb (3rd June 1940)

I have appointed Mr W.S. Stephenson to take charge of my organisation in the USA and Mexico. As I

have explained to you, he has a good contact with an official who sees the President daily. I believe

this may prove of great value to the Foreign Office in the future outside and beyond the matters on

which that official will give assistance to Stephenson. Stephenson leaves this week. Officially he will

go as Principal Passport Control Officer for the USA. I feel that he should have contact with the

Ambassador, and should like him to have a personal letter from Cadogan to the effect that it may at

times be desirable for the Ambassador to have personal contact with Mr Stephenson.

(6) Adolf Berle, letter to Sumner Welles (31st March, 1941)

The head of the field service appears to be Mr. William S. Stephenson… in charge of providing

protection for British ships, supplies etc. But in fact a full size secret police and intelligence service is

rapidly evolving… with district officers at Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston,

New Orleans, Houston, San Francisco, Portland and probably Seattle….

I have in mind, of course, that should anything go wrong at any time, the State Department would

be called upon to explain why it permitted violation of American laws and was compliant about an

obvious breach of diplomatic obligation… Were this to occur and a Senate investigation should

follow, we should be on very dubious ground if we have not taken appropriate steps.

(7) Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service: 1909-1949 (2010)

Stephenson arrived in New York to take over as Passport Control Officer on Friday 21 June 1940. The

following day France signed an armistice with the Germans, leaving Britain and the empire to stand

alone. The official history of what became (from January 1941) British Security Co-ordination, which

Stephenson had caused to be compiled in 1945, states that, before he left London, he “had no

settled or restrictive terms of reference”, but that Menzies “had handed him a list of certain

essential supplies” which Britain needed. Menzies also laid down three primary concerns: “to

investigate enemy activities, to institute adequate security measures against the threat of sabotage

to British property and to organize American public opinion in favour of aid to Britain”. With his

headquarters on the thirty-fifth and thirty-sixth floors of the International Building in the

Rockefeller Center, 630 Fifth Avenue, Stephenson built up a very extensive organisation, recruiting

many staff from his native Canada, although Menzies sent the intelligence veteran C. H. (Dick) Ellis

to be his second-in-command. The New York organisation expanded well beyond pure intelligence

matters, and eventually combined the North American functions not just of SIS, but of M15, SOE and

the Security Executive (which existed to co-ordinate counter-espionage and counter-subversion

work): intelligence, security, special operations and also propaganda. Agents were recruited to

target enemy or enemy controlled businesses, and penetrate Axis (and neutral) diplomatic

missions; representatives were posted to key points, such as Washington, New Orleans, Los

Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle; American journalists, newspapers and news agencies were

targeted with pro-British material; an ostensibly independent radio station (WURL), “with an

unsullied reputation for impartiality”, was virtually taken over; and close liaison was established

with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Stephenson also ran special operations throughout the

western hemisphere and from July 1942 to April 1943 was put in charge of all SIS’s South American

stations.

(8) Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948)

There was, by Roosevelt’s order and despite State Department qualms, effectively close cooperation

between J. Edgar Hoover and the F.B.I. and British security services under the direction of

a quiet Canadian, William Stephenson. The purpose of this co-operation was the detection and

frustration of espionage and sabotage activities in the Western Hemisphere by agents of Germany,

Italy and Japan, and also of Vichy France, Franco’s Spain and, before Hitler turned eastward, the

Soviet Union. It produced some remarkable results which were incalculably valuable, including the

thwarting of attempted Nazi Putsche in Bolivia, in the heart of South America, and in Panama.

Hoover was later decorated by the British and Stephenson by the U.S. Government for exploits

which could hardly be advertised at the time.

(9) Conversation between William Stephenson and President Franklin D. Roosevelt (February, 1943)

Roosevelt: “Could Bohr be whisked out from under Nazi noses and brought to the Manhattan

Project?”

Stephenson: “It will have to be a British mission. Niels Bohr is a stubborn pacifist. He does not

believe his work in Copenhagen will benefit the Germany military caste. Nor is he likely to join an

American enterprise which has as its sole objective the construction of a bomb. But he is in constant

touch with old colleagues in England whose integrity he respects.”

(10) Thomas F. Troy, Wild Bill and Intrepid: Donovan, Stephenson and the Origins of the CIA (1996)

Stephenson, then 73, showed the effects of a stroke: a cane, shuffling feet, a slightly closed left eye,

a curled upper lip, slightly slurred speech, and the years had made him heavier than the lightweight

of old. But he smiled readily, his handshake was firm, his eyes were bright, his voice was strong, and

his mind was active. Proof of his relative well being? On that first visit we and his wartime deputy

sat in undisturbed lively conversation for fully four hours.

(11) William Boyd, The Guardian (19th August, 2006)

“British Security Coordination”. The phrase is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps

some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was

generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history; a covert

operation, moreover, that was run not in Occupied France, nor in the Soviet Union during the cold

war, but in the US, our putative ally, during 1940 and 1941, before Pearl Harbor and the US’s

eventual participation in the war in Europe against Nazi Germany…

After the fall of France in June 1940, Britain’s position became even weaker – it was assumed that

British capitulation was simply a matter of time; why join the side of a doomed loser, ran the

argument in the US. Roosevelt’s hands were therefore firmly tied. Much as he might have liked to

help Britain (and this, I feel, is a moot point: just how enthusiastic was FDR himself?) he dared not

risk alienating Congress – and he had a presidential election looming that he did not want to lose.

To go to the country on a “Join the war in Europe” ticket would have been electoral suicide. He had

to be very pragmatic indeed – and there was no greater pragmatist than FDR.

All the same, Churchill’s task, as he himself saw it, was clear: somehow, in some way, the great mass

of the population of the US had to be persuaded that it was in their interests to join the war in

Europe, that to sit on the sidelines was in some way un-American. And so British Security

Coordination came into being…

Stephenson called his methods “political warfare”, but the remarkable fact about BSC was that no

one had ever tried to achieve such a level of “spin”, as we would call it today, on such a vast and

pervasive scale in another country. The aim was to change the minds of an entire population: to

make the people of America think that joining the war in Europe was a “good thing” and thereby

free Roosevelt to act without fear of censure from Congress or at the polls in an election.

BSC’s media reach was extensive: it included such eminent American columnists as Walter Winchell

and Drew Pearson, and influenced coverage in newspapers such as the Herald Tribune, the New York

Post and the Baltimore Sun. BSC effectively ran its own radio station, WRUL, and a press agency, the

Overseas News Agency (ONA), feeding stories to the media as they required from foreign datelines

to disguise their provenance. WRUL would broadcast a story from ONA and it thus became a US

“source” suitable for further dissemination, even though it had arrived there via BSC agents. It

would then be legitimately picked up by other radio stations and newspapers, and relayed to

listeners and readers as fact. The story would spread exponentially and nobody suspected this was

all emanating from three floors of the Rockefeller Centre. BSC took enormous pains to ensure its

propaganda was circulated and consumed as bona fide news reporting. To this degree its

operations were 100% successful: they were never rumbled.

Nobody really knows how many people ended up working for BSC – as agents or sub-agents or subsub-

agents – although I have seen the figure mentioned of up to 3,000. Certainly at the height of its

operations in late 1941 there were many hundreds of agents and many hundreds of fellow travellers

(enough finally to stir the suspicions of Hoover, for one). Three thousand British agents spreading

propaganda and mayhem in a staunchly anti-war America. It almost defies belief. Try to imagine a

CIA office in Oxford Street with 3,000 US operatives working in a similar way. The idea would be

incredible – but it was happening in America in 1940 and 1941, and the organisation grew and

grew…

One of BSC’s most successful operations originated in South America and illustrates the clandestine

ability it had to influence even the most powerful. The aim was to suggest that Hitler’s ambitions

extended across the Atlantic. In October 1941, a map was stolen from a German courier’s bag in

Buenos Aires. The map purported to show a South America divided into five new states – Gaus, each

with their own Gauleiter – one of which, Neuspanien, included Panama and “America’s lifeline” the

Panama Canal. In addition, the map detailed Lufthansa routes from Europe to and across South

America, extending into Panama and Mexico. The inference was obvious: watch out, America, Hitler

will be at your southern border soon. The map was taken as entirely credible and Roosevelt even

cited it in a powerful pro-war, anti-Nazi speech on October 27 1941: “This map makes clear the Nazi

design,” Roosevelt declaimed, “not only against South America but against the United States as

well.”

The news of the map caused a tremendous stir: as a piece of anti-Nazi propaganda it could not be

bettered. But was the South America map genuine? My own hunch is that it was a British forgery

(BSC had a superb document forging facility across the border in Canada). The story of its

provenance is just too pat to be wholly believable. Allegedly, only two of these maps were made;

one was in Hitler’s keeping, the other with the German ambassador in Buenos Aires. So how come a

German courier, who was involved in a car crash in Buenos Aires, happened to have a copy on him?

Conveniently, this courier was being followed by a British agent who in the confusion of the incident

somehow managed to snaffle the map from his bag and it duly made its way to Washington.

The story of the South America map and the other BSC schemes was written up (in an extensive

document of some hundreds of pages) after the war for private circulation by three former

members of BSC (one of them Roald Dahl, interestingly enough). This secret history was a form of

present for William Stephenson and a selected few others; it was available only in typescript and

only 10 typescripts ever existed. Churchill had one, Stephenson had one and others were given to a

few high officials in the SIS but they were regarded as top secret.

When Stephenson’s highly colourful and vividly inaccurate biography was written (A Man Called

Intrepid, 1976), the BSC typescript was drawn on by its author, but very selectively – in order to

spare American blushes. The story of BSC seemed to be one of those wartime secrets that was

never to be wholly revealed, like Bletchley Park and the Enigma machine decryptions. But the

Enigma story was eventually made public and has been written about endlessly since the mid-

1970s, fostering films, TV plays and novels in the wake of the revelations. But somehow BSC and the

role of British agents in the US before Pearl Harbor has remained almost wholly undisclosed – one

wonders why.

In 1998 the BSC typescript (one of only two remaining) was eventually published. To say it fell

stillborn from the press would be an understatement. Yet here is a book of some 500 pages, written

just after the war by former BSC agents, telling the whole story of Britain’s US infiltration in great

detail, recounting all the dirty tricks and the copious and widespread news manipulation that went

on. I think it’s fair to say that historians of the British Secret Services know about BSC and its

operations, yet in the wider world it still remains virtually unheard of.

The reason is the story of BSC and its operations before Pearl Harbor is deeply embarrassing and

remains so to this day. The document is explicit and condescending about American gullibility: “The

simple truth is the United States is inhabited by people of many conflicting races, interests and

creeds. These people, though fully conscious of their wealth and power in the aggregate, are still

unsure of themselves individually, still basically on the defensive.” BSC set out to manipulate “these

people” and was very successful at so doing – hardly the kind of attitude countries involved in a

“special relationship” should display. But that relationship is a Churchillian myth, invented and

fostered by him after the war, and has been bought into wholesale by every subsequent British

prime minister (with the possible exception of Harold Wilson).

As the secret history of the BSC unequivocally shows, sovereign states act exclusively to serve their

own interests. A commentator in the Washington Post who read the BSC history remarked, “Like

many intelligence operations, this one involved exquisite moral ambiguity. The British used ruthless

methods to achieve their goals; by today’s peacetime standards, some of the activities may seem

outrageous. Yet they were done in the cause of Britain’s war against the Nazis – and by pushing

America towards intervention, the British spies helped win the war.” Would BSC’s activities

eventually have encouraged the US to join the war in Europe? It remains one of the great “what ifs”

of historical speculation. The tide of US public opinion seemed to be turning towards the end of

1941 – though isolationist sentiments remained very strong – and BSC’s propaganda and relentless

news manipulation deserved much of the credit for that change but, in the event, matters were

taken out of BSC’s hands. On the morning of Sunday, December 7 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl

Harbor – the “day of infamy” had dawned and the question of American neutrality was gone for

ever.